Walt Disney Concert Hall design by Frank Gehry #architecture

© Frank Gehry

© Frank Gehry

© Frank Gehry

© Frank Gehry

© Frank Gehry

© Frank Gehry

© Frank Gehry

© Frank Gehry

© Frank Gehry

© Frank Gehry

© Frank Gehry

© Frank Gehry

© Frank Gehry

© Frank Gehry

© Frank Gehry

© Frank Gehry

© Frank Gehry

© Frank Gehry

© Frank Gehry

© Frank Gehry

© Frank Gehry

Architects: Frank Gehry

Location: 111 S Grand Ave, Los Angeles, CA

Design Partner: Frank Gehry

Project Partner: James Glymph

Project Manager: Terry Bell

Project Architects: David Pakshong, William Childers, David Hardie, Kristin Woehl

Senior Detailer: Vartan Chalikian Project Designer: Craig Webb

Structural Engineer: John A. Martin & Associates, Inc.

Mechanical Engineers: Cosentini Associates, Levine/Seegel Associates

Electrical Engineer: Frederick Russell Brown & Associates

Civil Engineer: Psomas & Associates

Acoustical Consultants: Yasuhisa Toyota and Nagata Acoustics, Inc., Charles M. Salter Associates, Inc.

Exterior Wall Consultant: Gordon H. Smith Corporation

Garden Designer: Melinda Taylor Garden Design

Landscape Architect: Lawrence Reed Moline Ltd. Organ Builders: Rosales Organ Builders, Inc., Glatter-Gotz Lighting Consultant: L’Observatoire

Graphics Consultant: Bruce Mau Design, Inc., Adams Morioka

Accessibility Consultant: Rolf Jensen & Associates

Theater Consultant: Theatre Projects Consultants, Fisher Dachs Associates

Client: Los Angeles Philharmonic

Area: 200000.0 ft2 , Year: 2003

Location: 111 S Grand Ave, Los Angeles, CA

Design Partner: Frank Gehry

Project Partner: James Glymph

Project Manager: Terry Bell

Project Architects: David Pakshong, William Childers, David Hardie, Kristin Woehl

Senior Detailer: Vartan Chalikian Project Designer: Craig Webb

Structural Engineer: John A. Martin & Associates, Inc.

Mechanical Engineers: Cosentini Associates, Levine/Seegel Associates

Electrical Engineer: Frederick Russell Brown & Associates

Civil Engineer: Psomas & Associates

Acoustical Consultants: Yasuhisa Toyota and Nagata Acoustics, Inc., Charles M. Salter Associates, Inc.

Exterior Wall Consultant: Gordon H. Smith Corporation

Garden Designer: Melinda Taylor Garden Design

Landscape Architect: Lawrence Reed Moline Ltd. Organ Builders: Rosales Organ Builders, Inc., Glatter-Gotz Lighting Consultant: L’Observatoire

Graphics Consultant: Bruce Mau Design, Inc., Adams Morioka

Accessibility Consultant: Rolf Jensen & Associates

Theater Consultant: Theatre Projects Consultants, Fisher Dachs Associates

Client: Los Angeles Philharmonic

Area: 200000.0 ft2 , Year: 2003

Photographs: Gehry Partners, LLP, Carlos Eduardo Seo, Matt Blanchard, Michael Smith, Philipp Rümmele, Kwong Yee Cheng, Jayson Oertel, Dave Toussaint,Andrew Barber, 2013 Los Angeles Philharmonic Association, G. Hanami, Stephen Bird, Filippo Vancini

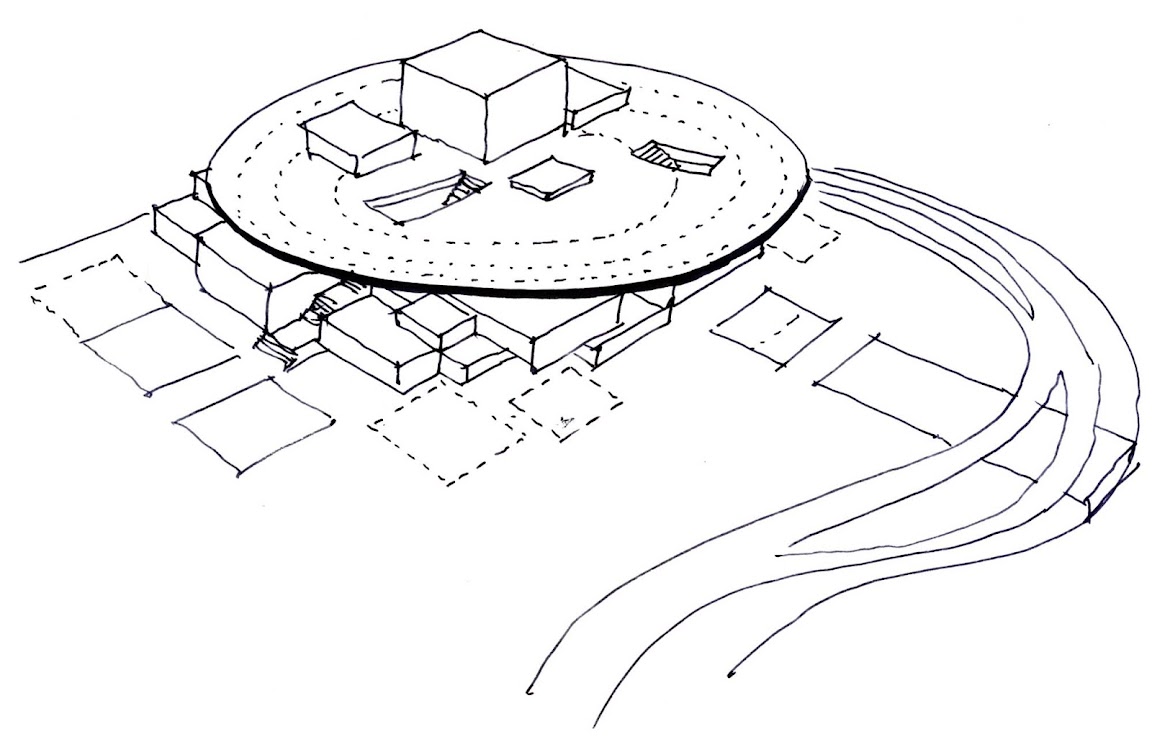

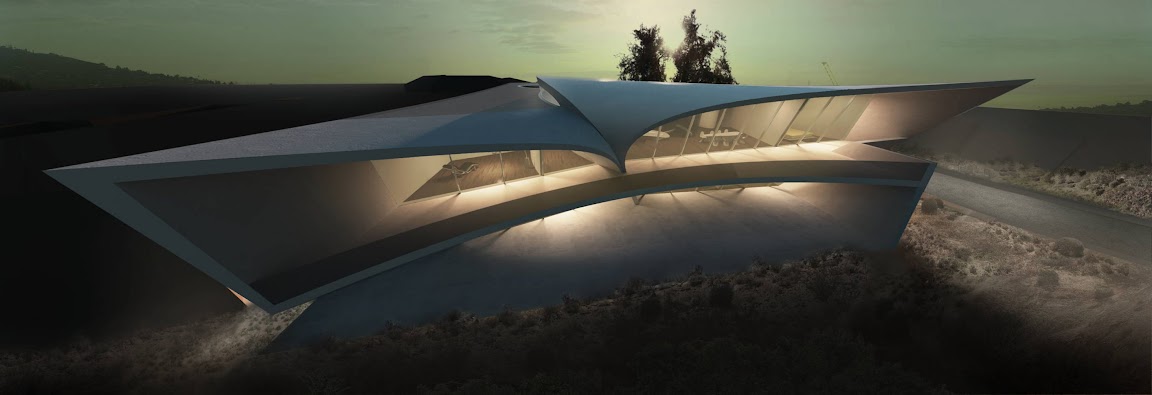

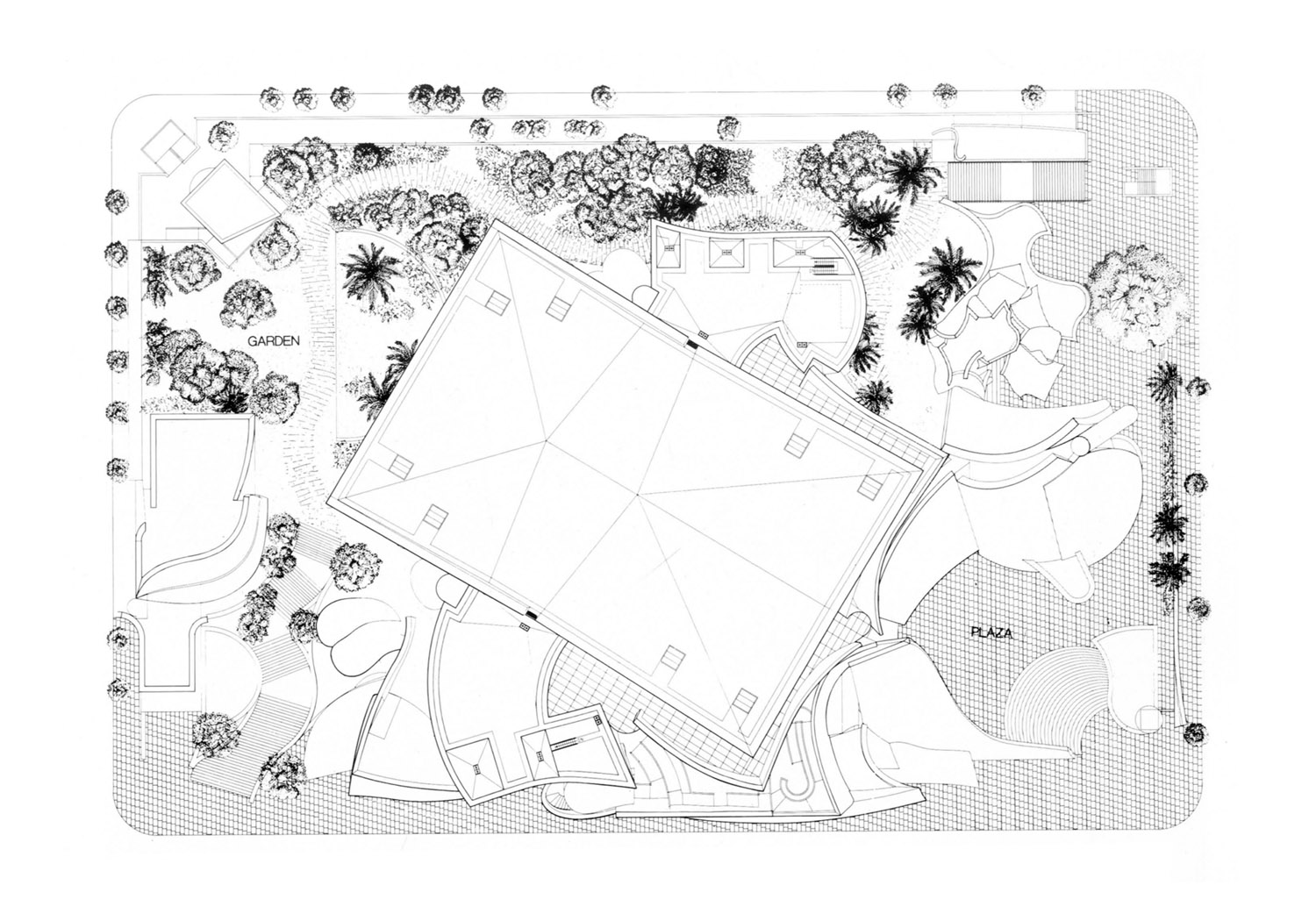

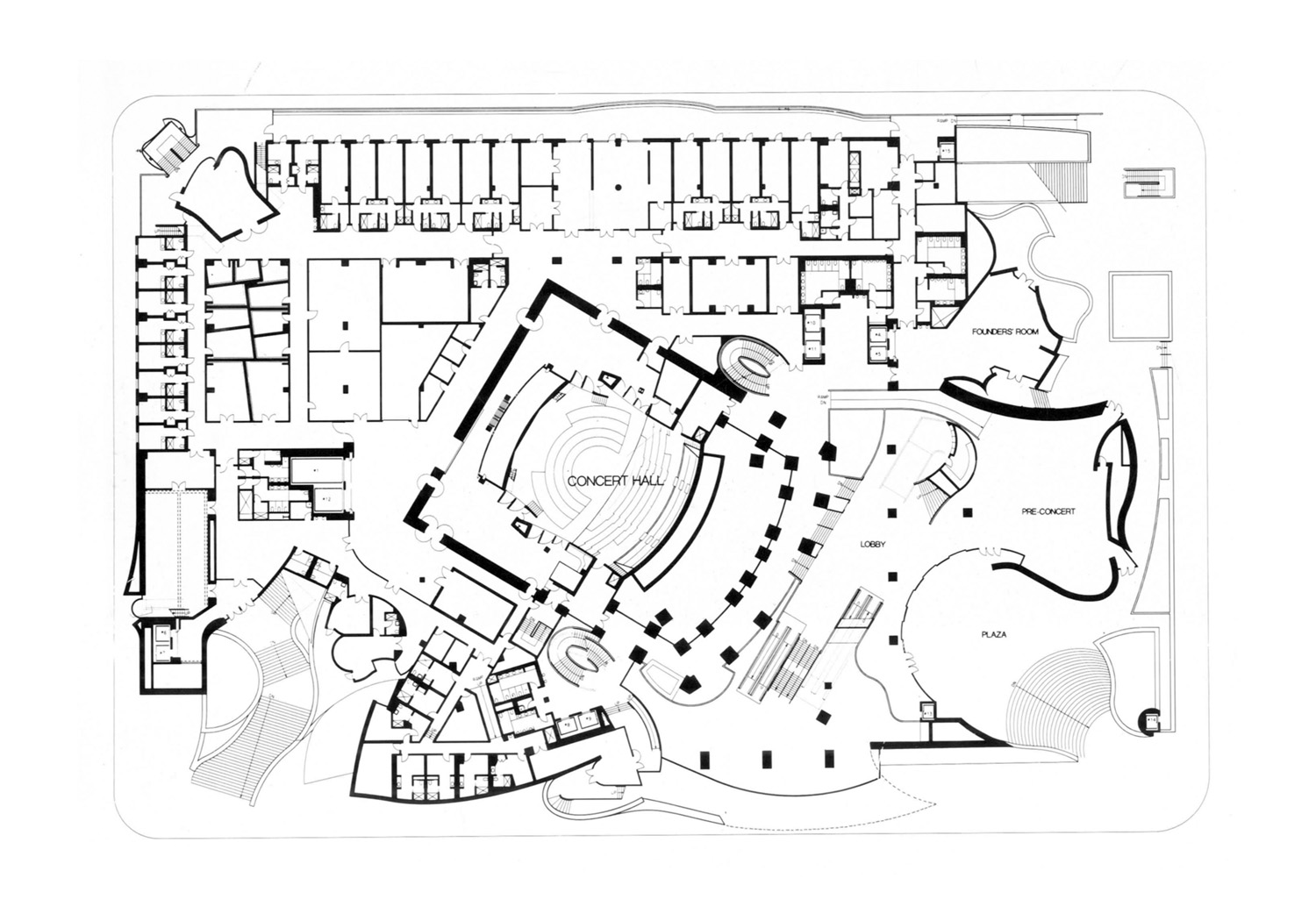

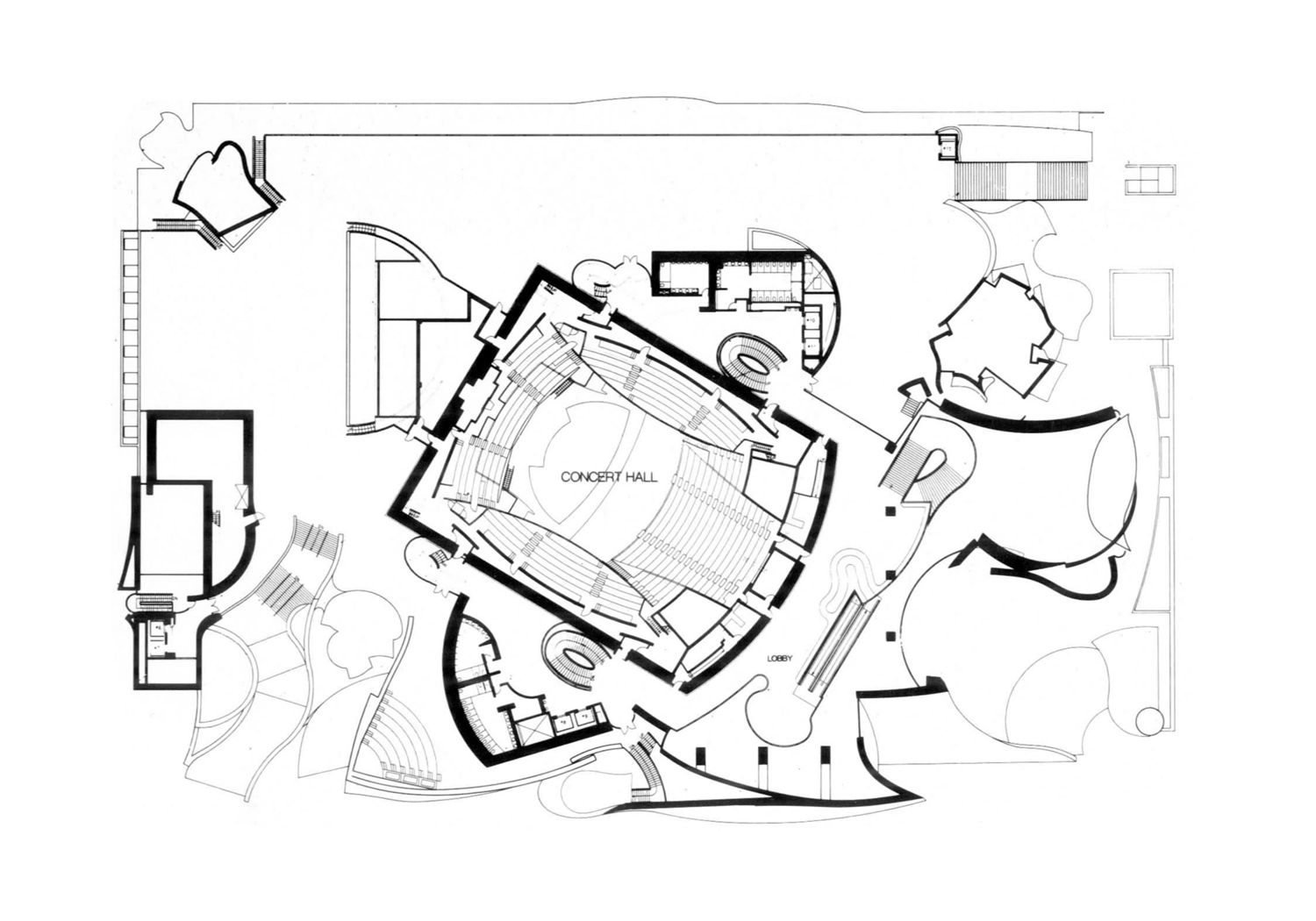

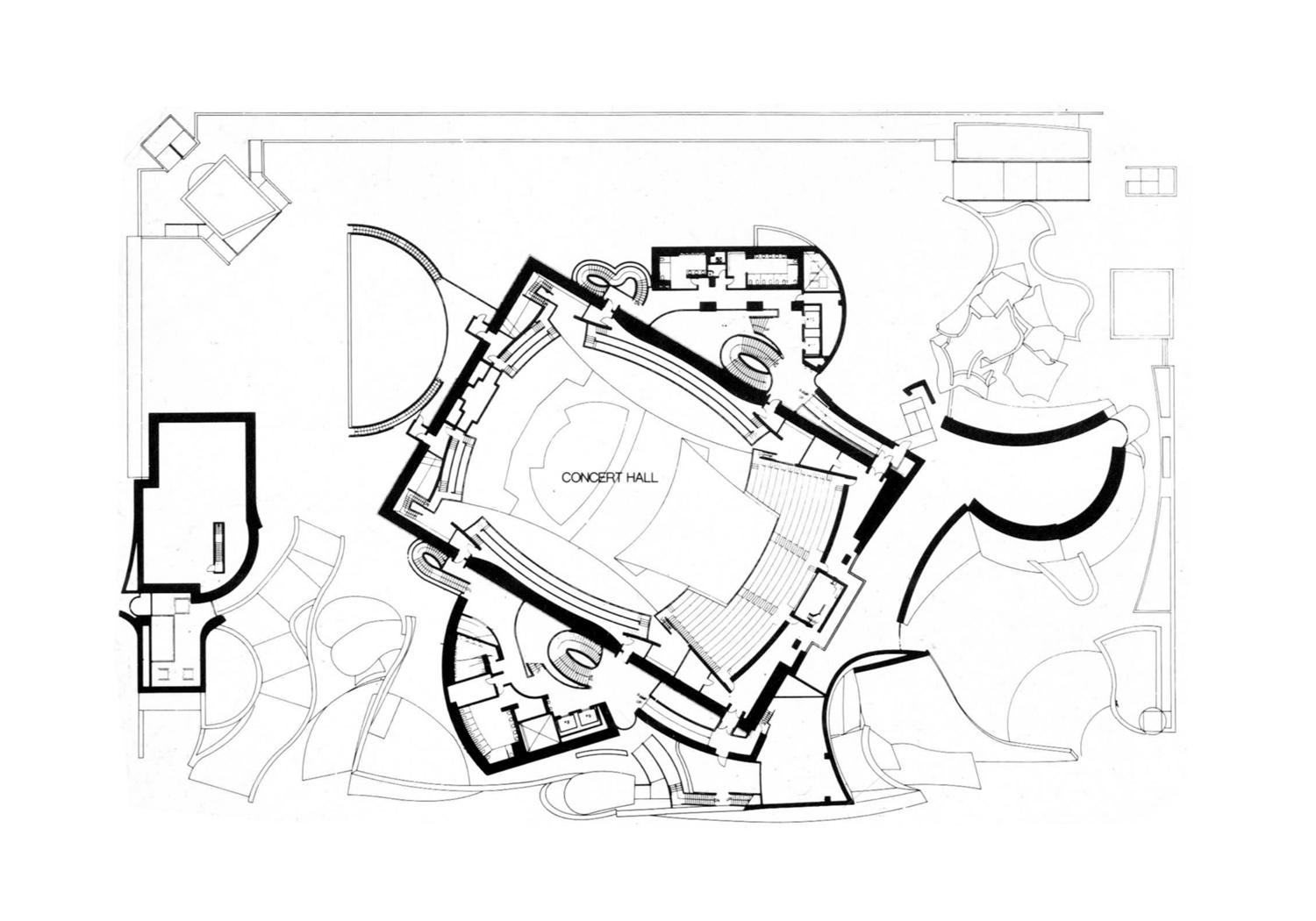

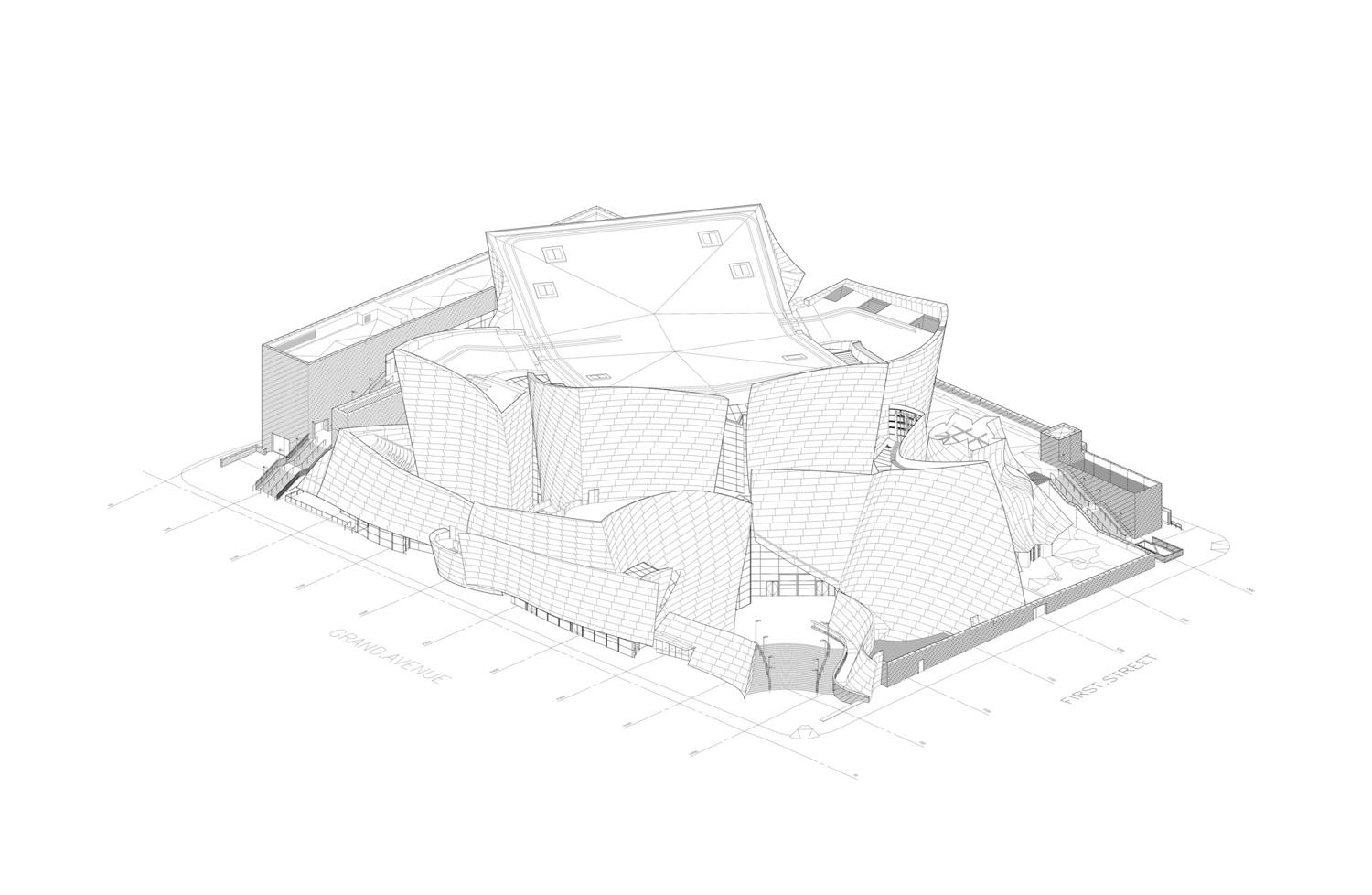

In 1987, Lilian Disney donated $50 million to establish a concert hall in honor of her late husband, Walt. Frank Gehry was selected from among several candidates during a design competition the following year. His proposal was largely oriented toward the public, with much of the site allocated to open gardens. Several years into the project, a combination of political and managerial impediments threatened its realization. It was shut down in 1994, but revived by a press and fund-raising campaign two years later. The concert hall was designed as a single volume, with orchestra and audience occupying the same space. Seats are located on each side of the stage, providing some audience members with distant views of the performers’ sheet music. The former director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic felt boxes and balconies implied social hierarchies within the audience, and spatial segregation was minimized in the design. Curvilinear planes of Douglas fir provide the only partitions, delineating portions of the 2,265 member audience without creating visual obstructions. The steel roof structure spans the entire space, eliminating the need for interior columns. The organ stands at the front of the hall, a bouquet of 6,134 curved pipes extending nearly to the ceiling. It is the unique result of a collaboration between Gehry and Manuel J. Rosales, a Los Angeles-based organ designer. Gehry worked with Yasuhisa Toyota, the acoustical consultant, to hone the hall’s sound through spatial and material means. To test the acoustics, they used a 1:10 scale model of the auditorium, complete with a model occupant in each seat. This required all elements to be scaled accordingly, including increasing the frequency of sound in the space to reduce the wavelength by a factor of ten. The concert hall’s partitions and curved, billowing ceiling act as part of the acoustical system while subtly referencing the sculptural language of the exterior. The exterior is a composition of undulating and angled forms, symbolizing musical movement and the motion of Los Angles. The design developed through paper models and sketches, characteristic of Gehry’s process. The custom curvature demanded a highly specific steel structure, including box columns tilted forward at 17º on the building’s north side. Visitors can glimpse the steel frame through a skylight in the pre-concert room and view the supporting structure from a stairway leading to the garden. The reflective, stainless steel surface engages light as an architectural medium. The facade’s individual panels and curves are articulated in daylight and colored by city lights after dark. The building was initially set to be clad in stone, but a more malleable material was chosen following the completion of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, the concert hall’s titanium-clad cousin. Thin metal panels allowed for more adventurous curvature and could be structurally disassociated from the ground. The metallic forms appear to hover above an asymmetrical band of glazing at the building’s base. Glass fissures in the facade bring light into the lobby and pre-concert room, reading as a grand entryway through the otherwise opaque facade. The hall’s planning committee conceived of the project as a civic amenity, hoping it would serve as a catalyst in the activation of LA’s downtown. Some critics debate the effectiveness of this siting strategy, acknowledging an increase in surrounding property values but little shift in the city’s cultural epicenter. Perhaps that will change as development continues on the site. The Diller Scofidio + Renfro designed Broad Museum is under construction across the street, and Gehry himself recently announced he will rejoin the effort to develop the adjacent stretch of Grand Avenue. There may be a cost to creating a cultural center beside the concert hall, however. A new subway is scheduled to run 125 feet beneath the lowest level of the concert hall, and may disrupt the acoustics of the internationally recognized performance space.

Source: Gehry Partners,

milimetdesign – Where the convergence of unique creatives

Since 2009. Copyright © 2023 Milimetdesign. All rights reserved. Contact: milimetdesign@milimet.com