Project: The Church on the Water

Location: Tomamu, Shimukappu, Kamikawa Subprefecture, Hokkaidō, Japan

Architects: Tadao Ando

Topics: Concrete in Architecture, Churches

Area: 520 m2

Completion Year: 1988

Photographs: Hirofumi Inaba, Yoshio Shiratori

"The horizon divides the sky from the earth, the sacred from the profane. The landscape changes its appearance from moment to moment. In that transition, visitors can sense the presence of nature and the sacred"_Tadao Ando 1

A Journey Through Design and Nature

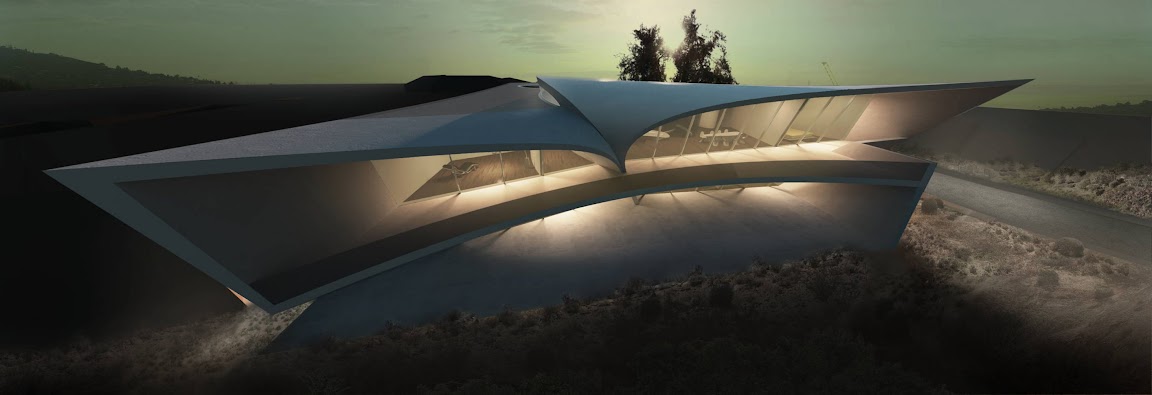

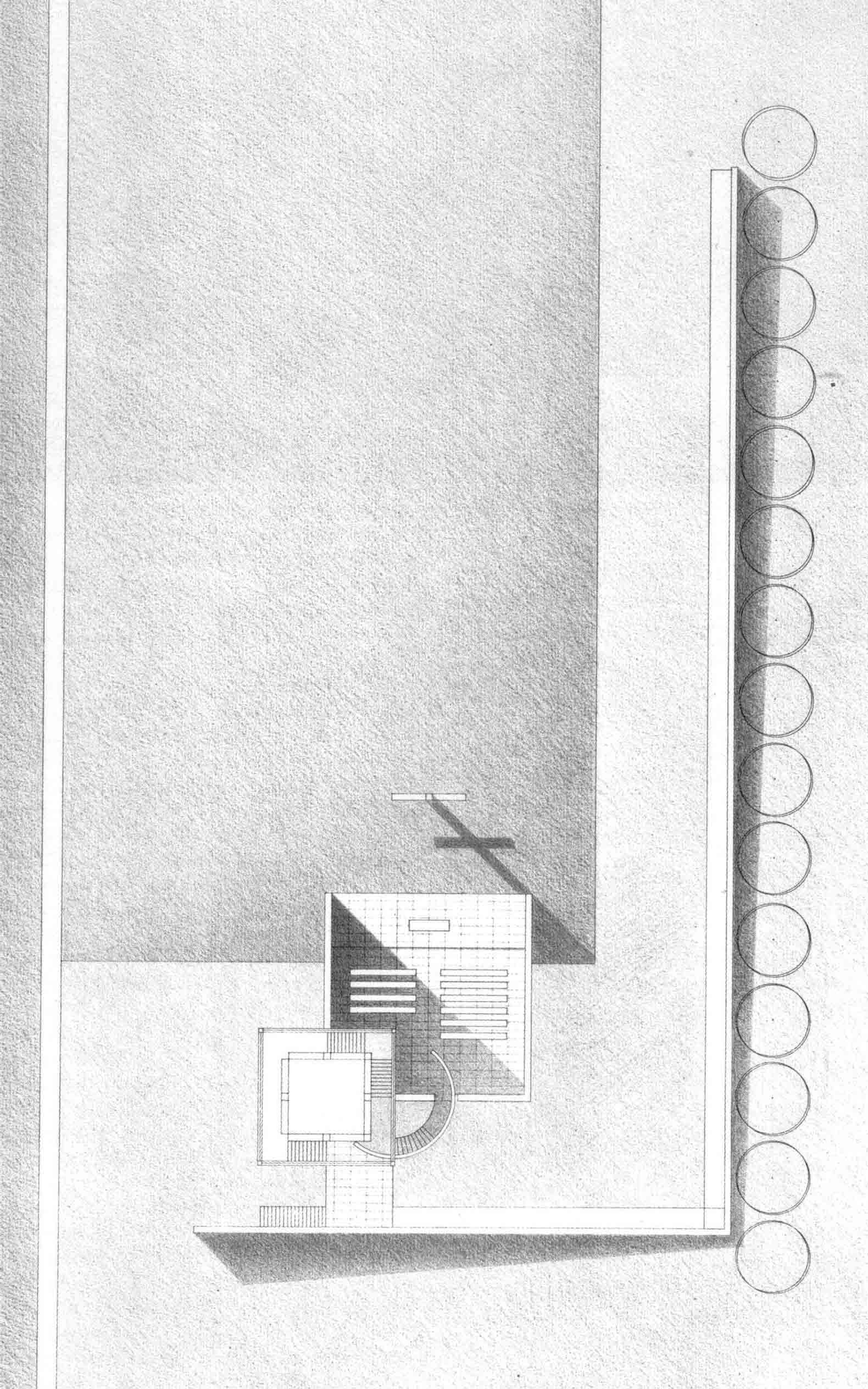

The Church on the Water was initially conceived for the Kobe coast, with the idea of a church floating on the sea, an audacious exploration of contrasts—solid structure against fluid Water, the sacred against the profane. However, when a landowner in Tomamu encountered the project, he saw the potential for a more intimate relationship with nature, leading to the church’s relocation to its current site in the isolated, verdant landscape of Hokkaidō.

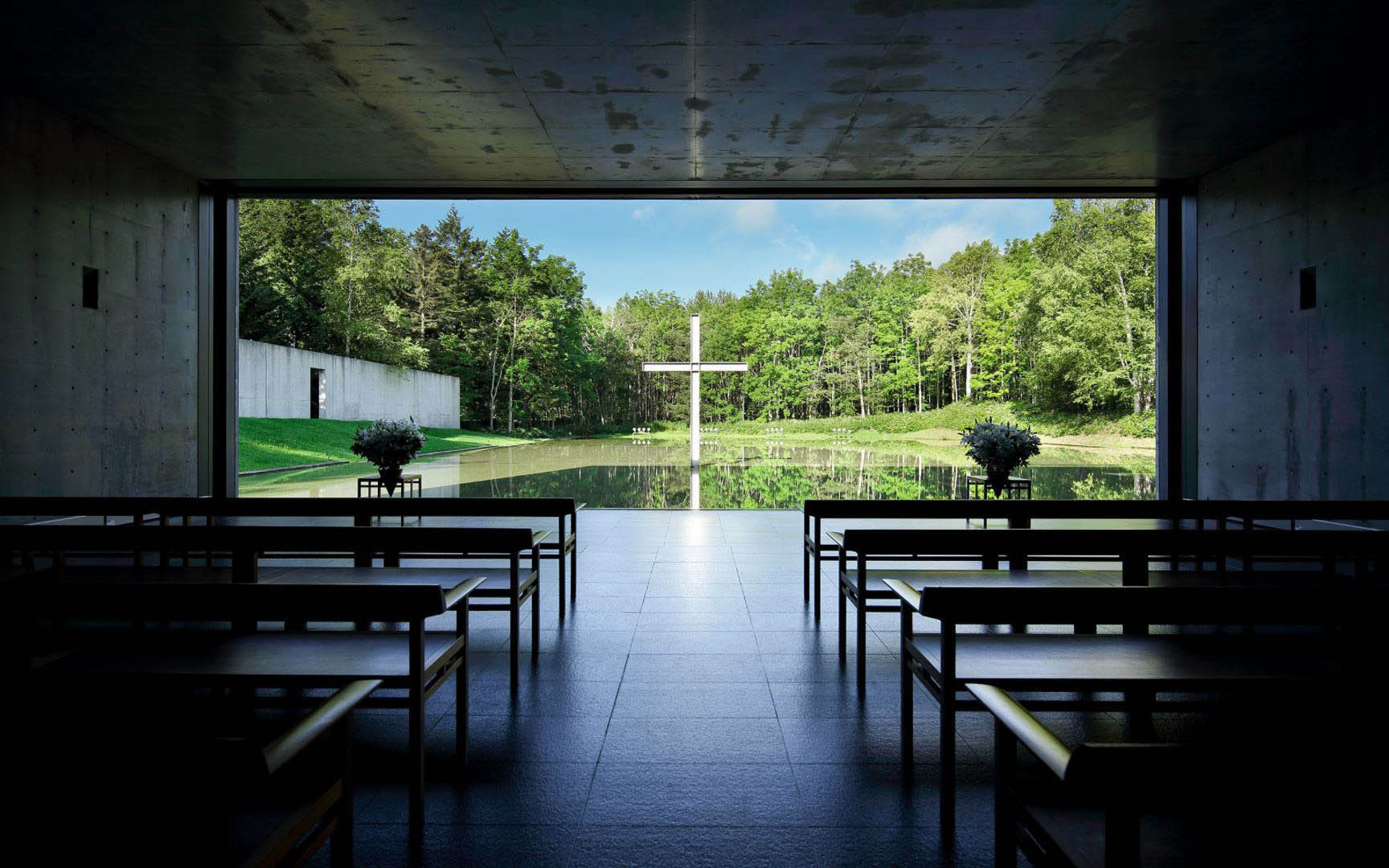

This change in setting did not diminish the project’s essence. Instead, it amplified the interplay between architecture and nature. The absence of the sea led Ando to replace the envisioned ocean with a tranquil pond, allowing the steel cross to float serenely on the still water. This created a powerful symbol of the church’s spiritual grounding amidst the ever-changing natural world.

The Ritual of Approach

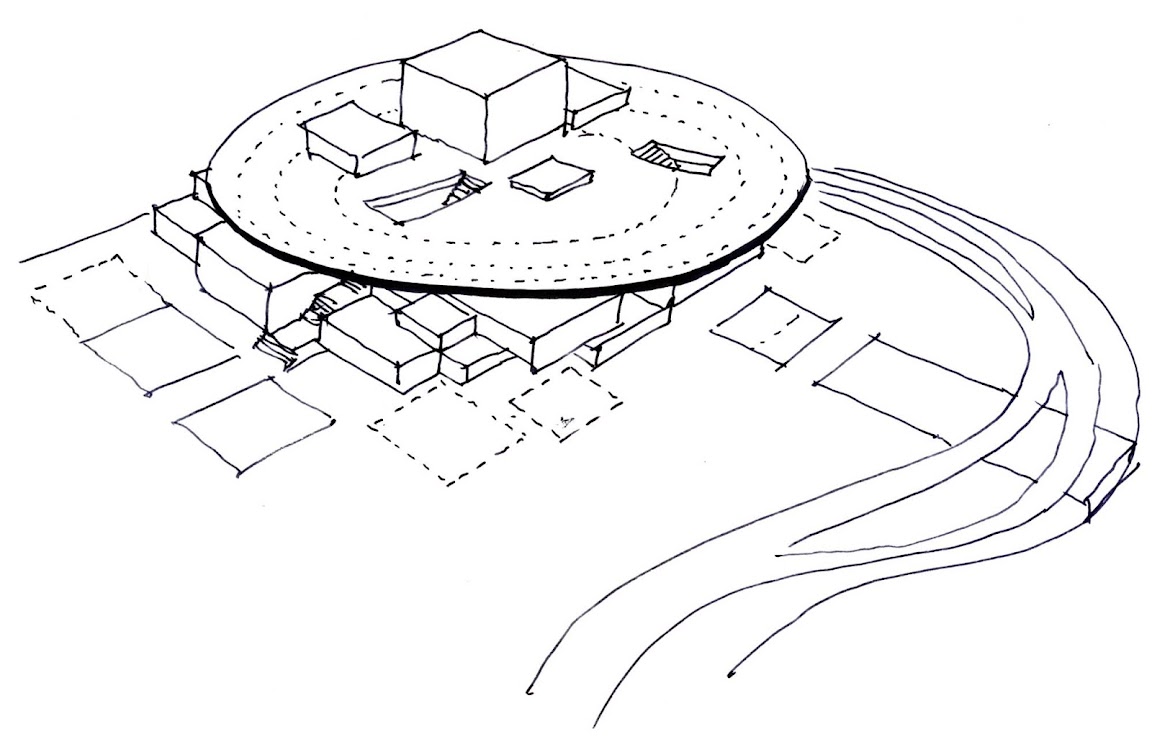

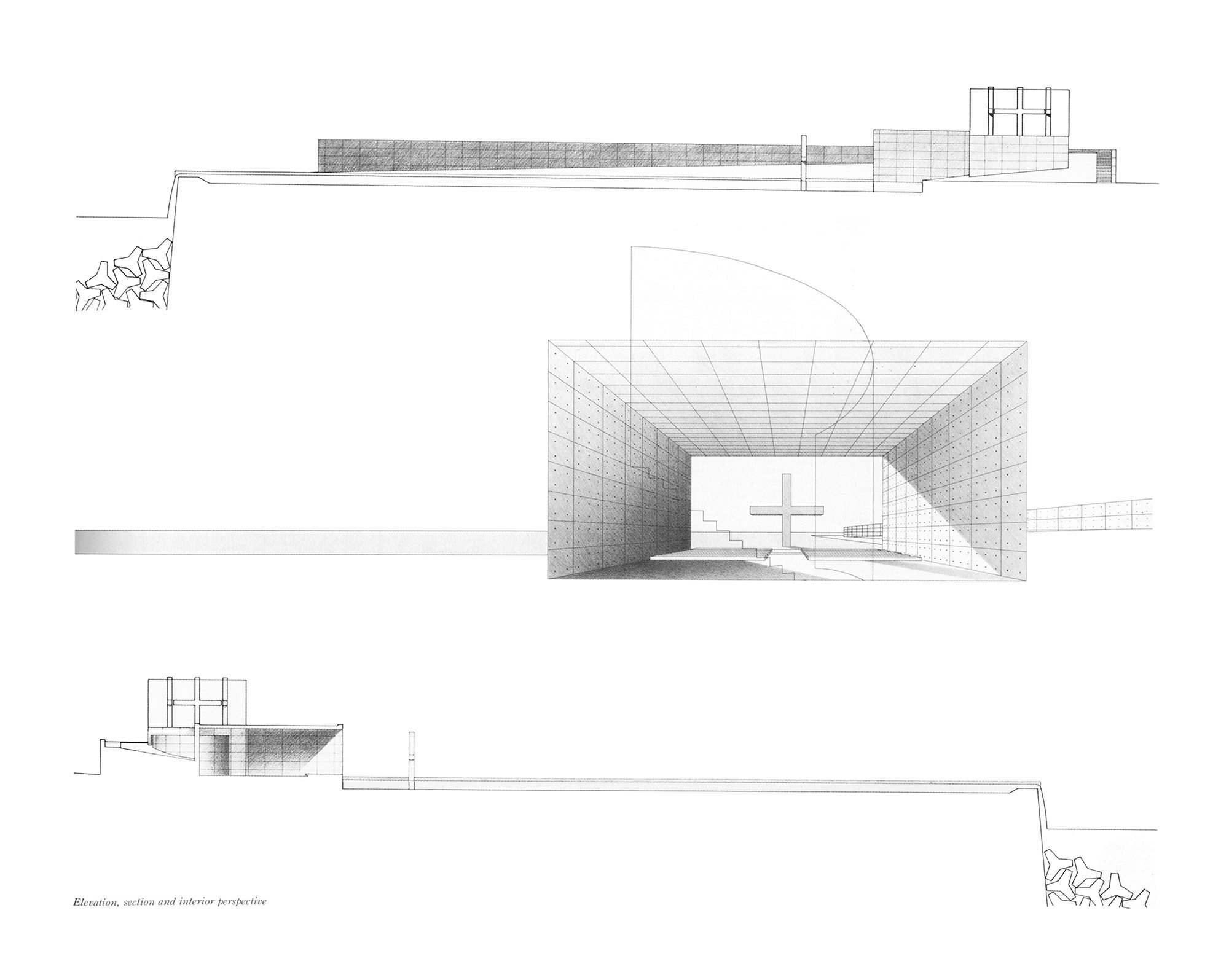

Ando’s architecture often involves a journey, both physical and spiritual. The Church on the Water exemplifies this approach. Visitors are not immediately presented with the church; instead, they embark on a carefully orchestrated procession. The path leads around an “L”-shaped wall that conceals the view of the pond, heightening the anticipation. The walk is not just a physical journey but a metaphorical purification, a preparation to encounter the sacred.

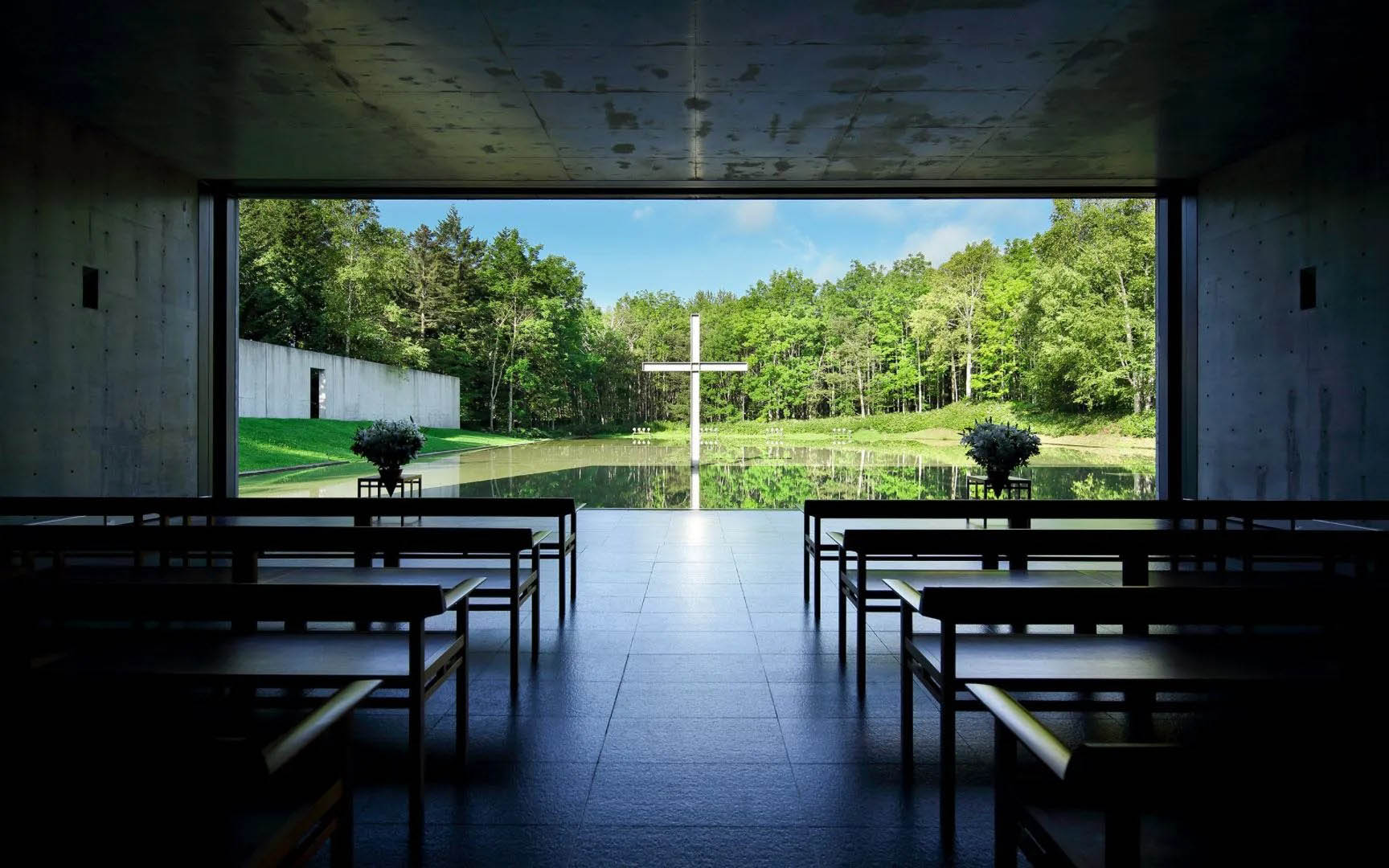

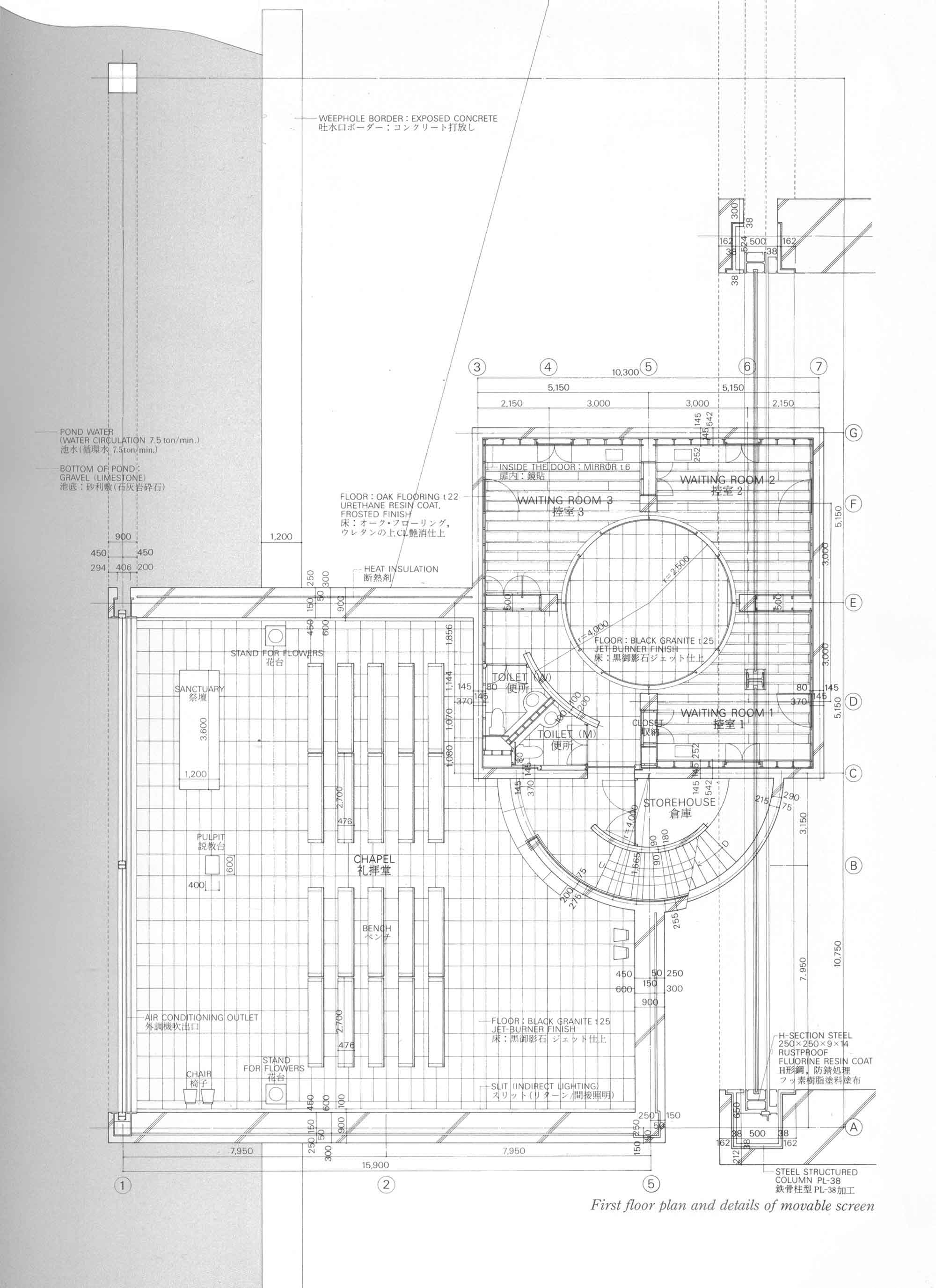

Upon entering the church, visitors are enveloped in an interplay of light and shadow, a hallmark of Ando’s work. The space is defined by its material simplicity—reinforced concrete and glass—but it is the manipulation of natural light that transforms it into a sacred environment. Four concrete crosses rise within the glass-encased entrance, their presence accentuated by the sunlight filtering through. The journey continues down a spiral staircase, bringing the visitor to the chapel where the dramatic reveal of the cross over the Water occurs, completing the architectural pilgrimage.

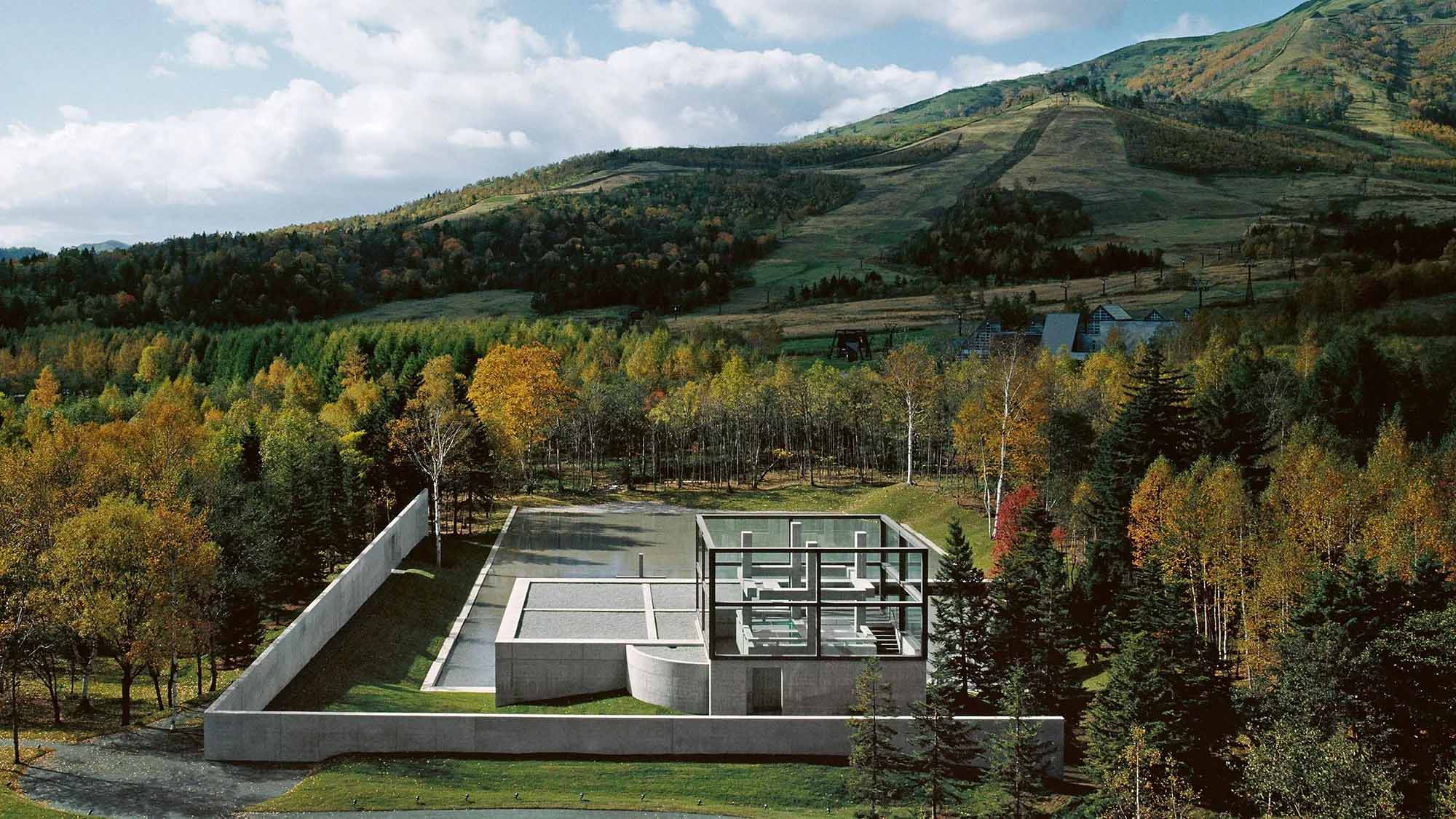

Materiality and Environment

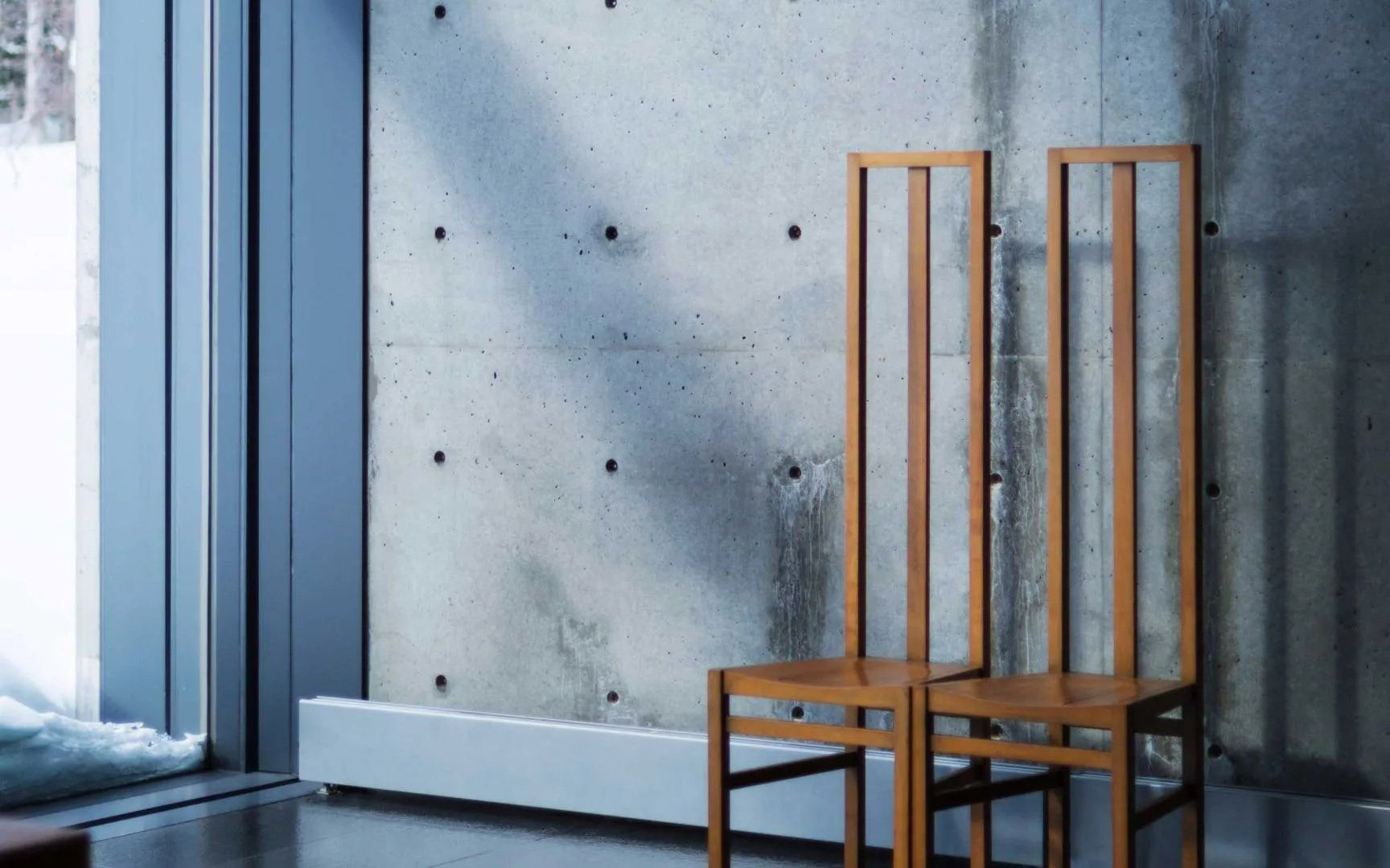

The material palette of the Church on the Water is quintessentially Ando—reinforced concrete and glass. However, the church’s concrete walls are not merely structural; they are performative. With a thickness of 900 millimeters, these walls incorporate thermal insulation to withstand Hokkaidō’s harsh winters. This practical consideration does not detract from the poetic intent of the building; rather, it reinforces Ando’s philosophy that architecture must engage with the realities of its environment.

The glass used both in the entrance volume, and the large window framing the pond allows nature to be an integral part of the interior experience. The shifting seasons play upon this glass, turning it into a canvas on which the natural world paints its ever-changing scenes—from the lush greens of summer to the stark whites of winter. The church becomes not just a place of worship but a place where one can witness and reflect upon the passage of time.

The Transcendent and the Temporal

Ando’s design does more than house a religious space; it elevates the relationship between the sacred and the natural. As Kenneth Frampton notes, Ando’s work often explores the “materiality of the ephemeral,”2 where the built environment is in constant dialogue with the transient forces of nature. The Church on the Water, with its ever-changing backdrop, is a manifestation of this dialogue.

In the winter, when the church is blanketed in snow, it appears almost otherworldly—a quiet sanctuary where the spiritual and the natural converge. This seasonal transformation is not merely aesthetic; it is integral to the experience of the architecture. As Tadao Ando himself reflects, the horizon divides not just the sky from the earth but the sacred from the profane. The church’s design invites visitors to sense this division and, in doing so, touch the transcendent.